Rebuilding Local Food Ecosystems

Food ecosystems as if people and planet mattered

The South Downs farm of the future can take a whole systems approach to designing a self-sustaining regenerative community farm that addresses food poverty, provides health and wellbeing services as well as ecosystem services to meet Carbon Neutral 2030 goals. This ecosocial farm model can provide the highest levels of carbon capture possible on farms, increasing soil fertility and biodiversity year by year while restoring hydrology and the vital protection of Brighton’s water supply. (Oxford Real Farming, 2022) Regenerative farms demonstrating ecosocial benefits already exist in the UK. Two of them are not far from Brighton, Tablehurst and Plawhatch biodynamic farms. Other noteworthy examples are CSA Stroud and The Apricot Centre at Huxhams Cross Farm in Devon.

How can such farms serve the most vulnerable communities in Brighton? The BH Food Partnership’s vision calls for a community-managed farm on the South Downs. The farms of the future could be partnered with Brighton’s most disadvantaged communities, inspired by the original CSA model, or Community Supported Agriculture. Food poverty and inequality is a big issue in Brighton. If design solutions are to be truly regenerative, they must create pathways for a just food system, upholding the human Right to food, Right to subsistence and Right to land access for food growing.

How can a Downland community farm achieve all this? One way is to design a model that takes land and food growing out of the commodity market, by bringing producer and consumer together to share the risks and benefits of providing responsibly grown food for the community. Stepping out of the free market, this new kind of farm, supported by community subscription, can also be a self-sustaining educational, social and ecological service to the city.

To understand this revolutionary concept, we need to revisit the deep-rooted convictions that gave rise to the CSA movement of the 1980s. In the UK, CSA has become a catch-all term for anything that involves community engagement, from veg boxes, community gardens to farmer’s markets. It is commonly misunderstood as simply a marketing strategy for veg boxes.

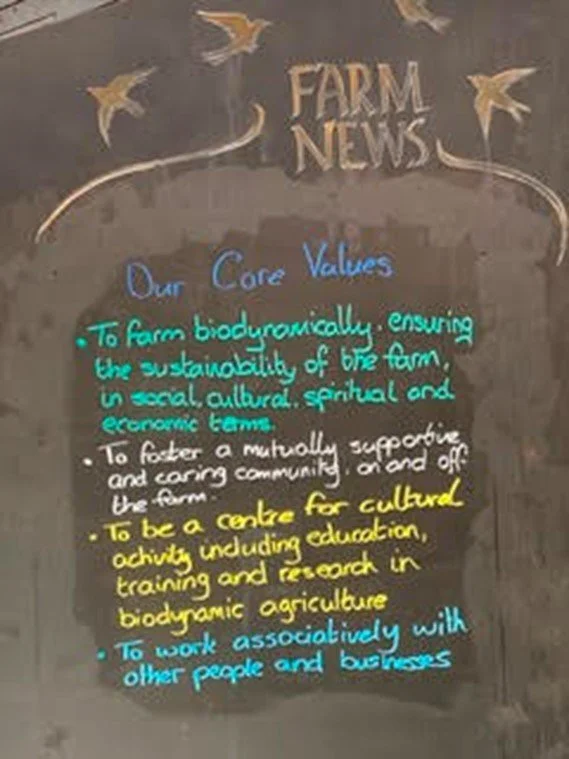

However, the original CSA was a radical response to the State-Economy hegemony, conceived by a group of biodynamic farmers seeking to protect the integrity of their farms and livelihoods and to uphold their mission of providing affordable organic food for the community.

“Important elements embedded into the CSA model, such as that of shared risk among members, make the arrangement more than merely transactional. In fact, the origins of the CSA movement in America have radical roots, drawn from the prominent environmental movement and a subculture dissatisfied with the prevailing economic system.” (Spears, 2022)

To support Brighton’s need for solutions to “local food security and food sovereignty as principles of climate action and economic justice,” it is worth exploring the transformative potential of the CSA model as grasped by those who first put the idea into action.

…The community-supported farming movement popularized in the 1980s had multiple antecedents around the globe…from Chile, to Japan, to rural Black communities in the Southern US, this movement may be best thought of as a spontaneous, distributed reaction to the conditions of globalized food markets. At the same time, growing concern around the health impacts of chemical pesticides, as well as the environmental costs of fossil fuel-based fertilizers, added impetus to the organization of organic farming at a more human scale. (Ibid.)

The ethos and organising principles of the formalised CSA model were documented by the American farmer Jan Vander Tuin, based on inspiring models he encountered in Switzerland. Co-founding the CSA movement with Robyn Van En of Indian Line Farm in Massachusetts, Vander Tuin observed that the idea of consumers personally cooperating with producers to fund farming in advance “makes for more efficient use of land…and much less stress for farmers…” Organic farming for direct local consumption becomes not just economical, but also more elegant and communal. (Ibid.)

The CSA model was motivated by a feeling “that existing food infrastructures are hopelessly entangled in the societal/cultural systems, especially the ‘free’ market.” In the Swiss examples, he noted how “concerned consumers and frustrated food workers” did not wait for top down solutions but undertook the responsibility of growing organic food for themselves. Shared values—such as organic growing and energy-conscious distribution—were identified from the outset. Everything down to how shares were calculated—based on the amount of produce the average non-vegetarian consumes per year— underscores the ambition for local self-reliance in food production. The document also highlights a strong desire for economic fairness at every step in CSA practices. The costs of start-up investment and land would “ideally…be divided up equally (or by sliding scale).” …“The emphasis in all economic thinking,” it concludes, “was not to work the maximum profit principle but on the need/cost coverage principle. This meant more trust and more participation.” (Ibid.)

Articulating the ‘Ideals of Community Supported Agriculture’ for a CSA manual, Robyn Van En underlines the deep-rooted values of the movement.

Agriculture… is the mother of all our culture and the foundation of our well-being. Modern farming…driven by purely economic considerations, has driven the culture out and replaced it with business: agriculture has become agribusiness… Our ideals for agriculture come to expression in the biodynamic method of farming which seeks to create a self-sustaining and improving ecological system in which…everything has its place in the cycle of the seasons…The community involvement in the rhythms of the seasons and the celebrations connected with them will also enable us to find our proper spiritual connection to nature again. (Ibid.)

Growing healthy, ecologically-sound food locally is, for a multitude of reasons, the most economical way for a community to provide for this most elemental of needs. Cutting out intermediaries and import dependency is a cornerstone of community food security and food sovereignty. The CSA model invites us to reconsider how we place a value on food growing and land itself, beyond the commodity market -- land and soil as our living infrastructure, as a natural asset, ecosystem service and health and wellbeing service for all. Land not as commodity but as our ecological commons. As the City Downland Estate Plan states, “This land is ours.” (B&H City Council, 2020) Can this statement truly serve Brighton residents who need to practise their Right to subsistence, their Right to food?

In the UK, Stroud Community Agriculture is a pioneering example of a food commons based on the original CSA impulse. Financed by upfront support from the community, it operates as a not-for-profit cooperative. All members have equal say in its management. Three hired farmers undertake practical farming decisions, while overall policy decisions are held by an elected core group. At some CSA farms, the practice is for farmers to present a budget to member households at the start of the growing season. Members then pledge how much they can pay, with those who have much giving more than those who have less, “not according to a formula, but according to each (household’s) sense of what is affordable and appropriate.” (Groh and McFadden, 1990) It is an expression of a solidarity economy.

The CSA model can only succeed with a committed group of producers and community members motivated by shared values and a willingness to develop strong working relationships through all the challenges that such initiatives may bring. In Brighton, the idea of a South Downs farm in partnership with a disadvantaged community would be greatly helped if the community has an established food hub or coop, with food justice and education programmes and strong leadership behind it, such as The Bevy Cooperative Pub, The Old Boat Corner and the Whitehawk Community Food Project.

Community land trust model

To secure the future of City Downland Estate land for sustainable, regenerative farming, thus also protecting the future of Brighton’s aquifer, BH City Council could consider adopting the innovative Community Land Trust model for its farms. In the UK, the Biodynamic Land Trust (BDLT) is such a model, securing the biodynamic future of farmland and offering affordable terms to committed farmers. The BDLT family of farms includes Brambletye Fields at Tablehurst and Springham Farm in Sussex, Oakbrook Community Farm in Stroud, the Apricot Centre at Huxhams Cross Farm in Devon and others. (Biodynamic Land Trust, website)

Pathways for food and social resilience

Combined with agroecological farming methods, ecosocial agriculture holds great potential in our efforts to address climate change, human and planetary health and social equity. Brighton can learn from the pioneering legal framework of Italy, where social agriculture was embedded in law in 2015. An Italian study on ecosocial agriculture for social transformation and environmental sustainability finds that a holistic view of the person, nature and the region is common to all approaches, with many initiatives opting for organic or biodynamic as well as traditional cultivation methods. The study notes that in this setting, the overarching concept of biodiversity transcends the agricultural realm to embrace the social dimension. (Nicli, Elsen and Bernhard, 2020)

Social farming for people with learning disabilities has been quietly practiced in Britain since 1939, when the first Camphill community was established in Scotland by a group of Austrian political refugees led by the visionary doctor, Karl Koenig. The care farm movement emerged from the Camphill biodynamic farm model in the UK. Today, Camphill is a worldwide movement dedicated to building communities where everyone can find purpose and belonging. Close to Brighton is The Mount Camphill Community in Wadhurst, a beautiful residential community where biodynamic farming is integral to the curative education of students with learning disabilities. This, and other aspects of the Camphill approach, invite further study from a social innovation and therapeutic community perspective. (The Mount Camphill, website)

Reconnecting people around the growing of their food opens pathways for food and social resilience, healing our widespread sense of disconnection from nature and community. It offers the promise for communities to rediscover how working in harmony with Nature, rather than seeking to exploit it, can be as economical as it is restorative, for people and planet.

What kind of institutions must exist for people to be able to have the right thoughts on social matters, and what kind of thoughts must exist that these right social institutions can arise?

– Rudolf Steiner